FOAL (Vernon Watkins)

Darkness is not dark, nor sunlight the light of the sun

But a double journey of insistent silver hooves.

Light wakes in the foal's blind eyes as lightning illuminates corn

With a rustle of fine-eared grass, where a starling shivers.

And whoever watches a foal sees two images,

Delicate, circling, born, the spirit with blind eyes leaping

And the left spirit, vanished, yet here, the vessel of ages

Clay-cold, blue, laid low by her great wide belly the hill.

See him break that circle, stooping to drink, to suck

His mother, vaulted with a beautiful hero's back

Arched under the singing mane,

Shaped to her shining, pricked into awareness

By the swinging dug, amazed by the movement of suns;

His blue fellow has run again down into grass,

And he slips from that mother to the boundless horizons of air,

Looking for that other, the foal no longer there.

But perhaps

In the darkness under the tufted thyme and downtrodden winds,

In the darkness under the violet's roots, in the darkness of the pitcher's music,

In the uttermost darkness of a vase

There is still the print of fingers, the shadow of waters.

And under the dry, curled parchment of the soil there is always a little foal

Asleep.

So the whole morning he runs here, fulfilling the track

Of so many suns; vanishing the mole's way, moving

Into mole's mysteries under the zodiac,

Racing, stopping in the circle. Startled he stands

Dazzled, where darkness is green, where the sunlight is black,

While his mother, grazing, is moving away

From the lagging star of those stars, the unrisen wonder

In the path of the dead, fallen from the sun in her hooves,

And eluding the dead hands, begging him to play.

© The Estate of Vernon Watkins. Used by kind permission of Gwen Watkins.

For this entry I'd like to specially thank Gwen Watkins for giving me permission to reproduce one of her late husband's poems, and also John Rhys Thomas for his assistance. The painting is by Stubbs, another horsey favourite.

I think that I encountered Vernon Watkins' 'Foal' at one of those particularly impressionable moments which came quite often between the ages of 10 and 20 in particular - or perhaps I should say 7 and 24... I think that my artistic interests since then have been mainly an extension of everything that came before. When I was 18 or 19 I was studying modern British poetry in one of my classes at university, and while this was not one of the poems we studied, it was in the Oxford anthology that we were using.

I have loved horses for a very, very long time, particularly since reading Marguerite Henry's King of the Wind when quite young. I was the quintessential horse-obsessed little girl, reading everything I could lay my hands on, writing bad poetry, and riding for several years until my studies and other aspects of life became more demanding. I am pretty sure that this poem came particularly to my notice during my browsing because it was about a foal. Vernon Watkins was a completely unfamiliar name to me. But I loved the poem so much that I ended up reading it to the class during a session where we all chose a poem to share. I've been reading Watkins on and off ever since.

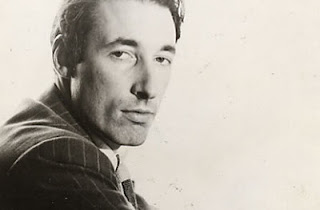

Vernon Watkins is best known today for having been a close friend of Dylan Thomas, not for his own poetry. What is less well known is the fact that Thomas described Watkins as "the most profound and greatly accomplished Welshman writing poems in English." Despite their friendship, they seem to have been two utterly different people: Thomas was a pure sensualist in both life and poetry, while Watkins was a deeply religious man with a stable and happy family life, influenced by the Symbolists and his Christian faith. Watkins' poems are pure and almost naive by comparison with those of Dylan Thomas. Notably, Thomas was supposed to be the best man at Watkins' wedding but failed to show up. At the time of Watkins' death, he was a strong candidate for the next British Poet Laureate. Sadly, he was only 61 when he died, and perhaps if he had lived longer and become the Poet Laureate he would be better known to the current generation. However, it is good to know that a New Selected Poems has been published in recent years by Carcanet and is available on this link.

I love Wales, although I have mainly travelled in Snowdonia, and Watkins was from South Wales (the Gower Peninsula). Gwen Watkins said of this poem: "We lived on the Gower cliffs for most of our married life, and at that time the wild ponies ran about the cliffs all the year round, so that in the spring there were many foals. Vernon knew every inch of Gower, and all its flowers, birds and animals." Watkins obviously had a profound love and reverence for the Welsh landscape. There are passages in his poems which crash across the reader's sensibilities like a wave on a headland:

Late I return, O violent, colossal, reverberant, eavesdropping sea.

My country is here. I am foal and violet. Hawthorn breaks from my hands.

(taken from 'Taliesin in Gower')

In other poems, colours and animal images create a powerful tapestry-like impression:

The mound of dust is nearer, white of mute dust that dies

In the soundfall's great light, the music in the eyes,

Transfiguring whiteness into shadows gone,

Utterly secret. I know you, black swan.

(taken from 'Music of Colours: White Blossom')

In his poems the animals and flowers are more than nature; they symbolize spiritual truths. I remember reading about 'Foal' and its companion poem 'The Mare', that Watkins had an interest in Plato's theory of the ideal form, whereby everything in the material world is only an echo or copy of a purer, perfect form on a spiritual plane. This could partly account for the description in 'Foal' of the "left spirit" and the "blue fellow" of the very real little foal who runs through the poem. The whispering image of "the print of fingers, the shadow of waters" also makes me think of Genesis and the early moment of creation, as though God has left his signature: "there was darkness upon the surface of the watery deep" (Genesis 1:2).

Essentially, however, this is a poem that I still find deeply mysterious and beautiful, which I love no less because interpretation somewhat eludes me. In many respects there is no other animal poem which quite compares with it, for me. The movements of the foal - leaping, startling, sleeping - are marvellously observed. Almost fifteen years after first reading the poem, there are still lines in it which haunt me and which remain, enchantingly, just out of reach. Sometimes I think that the shadowy foal refers to a dead twin; sometimes it is the Platonic ideal; sometimes it seems like the beautiful dreams that can wash through both our sleep and our waking hours, and which poetry brings us a little bit closer to touching.