COURTYARDS IN DELFT (Derek Mahon)

— Pieter de Hooch, 1659

(for Gordon Woods)

Oblique light on the trite, on brick and tile —

Immaculate masonry, and everywhere that

Water tap, that broom and wooden pail

To keep it so. House-proud, the wives

Of artisans pursue their thrifty lives

Among scrubbed yards, modest but adequate.

Foliage is sparse, and clings; no breeze

Ruffles the trim composure of those trees.

No spinet-playing emblematic of

The harmonies and disharmonies of love,

No lewd fish, no fruit, no wide-eyed bird

About to fly its cage while a virgin

Listens to her seducer, mars the chaste

Perfection of the thing and the thing made.

Nothing is random, nothing goes to waste.

We miss the dirty dog, the fiery gin.

That girl with her back to us who waits

For her man to come home for his tea

Will wait till the paint disintegrates

And ruined dikes admit the esurient sea;

Yet this is life too, and the cracked

Outhouse door a verifiable fact

As vividly mnemonic as the sunlit

Railings that front the houses opposite.

I lived there as a boy and know the coal

Glittering in its shed, late-afternoon

Lambency informing the deal table,

The ceiling cradled in a radiant spoon.

I must be lying low in a room there,

A strange child with a taste for verse,

While my hard-nosed companions dream of war

On parched veldt and fields of rainswept gorse.

© Derek Mahon, 2011. Taken from New Collected Poems, published by The Gallery Press. Used by permission of the publishers.

By the time I was ten, and certainly by the time I had turned 20, my loving parents had dragged me through a great many of Europe's finest art galleries. I can only thank them, because this left me with exactly two choices: to hate art and to never set foot in another art gallery again if I could help it, or to love art and keep seeking it out for the rest of my life. Fortunately, the gamble paid off and I chose the latter. Given that I have ten left thumbs when it comes to anything like drawing or painting, my interest in the visual arts is purely second-hand (and, I admit, mostly confined to European art at least 150 years old), but at least I can appreciate it and I know what I like when I see it.

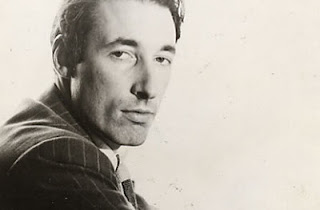

I think that the relationship between poetry and the visual arts is an uneasy one. It is difficult to convey the visceral impact of a great work of art using the written word, and I don't think that most paintings could incorporate the subtleties of a finely crafted poem. An outstanding exception is Derek Mahon's 'Courtyards in Delft'. It was inspired by the above painting by Pieter de Hooch, which hangs in London's National Gallery.

I racked my brains trying to remember when I first encountered Derek Mahon. Oddly enough, I think that his poem 'Ecclesiastes" appeared in an anthology which I used in my Canadian high school, but I don't remember studying it specifically. I probably started reading him more extensively when I lived in Ireland. I know that just before I moved from Ireland to England, I bought a copy of his new collection Harbour Lights, and by then I had already read at least some of his work. At any rate, somewhere over the years many of his poems got under my skin: the classics 'A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford' and 'The Mayo Tao', as well as personal favourites such as 'Kinsale' and 'The Chinese Restaurant in Portrush'. He is one of the great Northern Irish poets of the latter half of the 20th century, along with Seamus Heaney and Michael Longley. I have a theory that these Northern Irish poets and others are particularly memorable because they marry the Irish sense of mysticism to a more British formalism, but I'm not sure how far I would want to extend that idea.

I find 'Courtyards in Delft' particularly moving because it combines a loving (and slightly ironic) description of the painting with a more personal perspective, which could be very evocative even for someone who has not seen the painting. In his description of "Oblique light on the trite, on brick and tile—/Immaculate masonry", he succintly captures the clarity and serenity of the Dutch Golden Age of painting, which also included the likes of Vermeer, van Ruisdael and Hobbema. Humorously, he then notes the lack of suggestive symbols which are often included in paintings of the era, hinting at adultery, scorned love and drunken revelry: "We miss the dirty dog, the fiery gin." One could argue that the painting is just a little too serene. In the next stanza, however, he points out:

Yet this is life too, and the cracked

Outhouse door a verifiable fact

As vividly mnemonic as the sunlit

Railings that front the houses opposite.

There surely are moments in life when we feel serene and at peace, and when we perceive the beauty and even the holiness of everyday objects and situations. By his use of the word "mnemonic", suggesting an aid to memory, Mahon moves into the realm of his own childhood memories.

The concluding stanza of 'Courtyards in Delft' is for me one of the most touching that I have encountered in literature. Amazingly, at one and the same time it extends the description of the painting, touches on Mahon's own experiences, and reminds me of my own childhood. He describes sensory memories, the fall of light, the wonder that a child feels at seeing "the ceiling cradled in a radiant spoon". This reminded me of the summers I spent at my grandmother's house in Finland: looking through the different panes of the stained glass window at a world in red, or yellow, or green; the smooth-rough feeling of cobblestones under my bare feet; the dusk at midnight.

Mahon, like so many of us who felt somewhat isolated and different, was "a strange child with a taste for verse" (or literature generally, in my case...it would be more accurate to say that I am now a strange child with a taste for verse.) The "hard-nosed companions" of his childhood in Northern Ireland were probably dreaming of a bitter local struggle that has never entirely ended, but the feelings that Mahon describes are universal.

I often go to look at this painting when I visit the National Gallery. I am not sure if it is the painting that leads me to read the poem, or the poem that brings me to the painting. Probably the latter, a little more. It is just another example of how one great experience in the arts will inevitably lead me on to another.

In fact, I believe that great art can be a catalyst for many of life's most essential experiences. There will always be those who suggest that if you spend a lot of time with books, you're not really living life, and that one of the proofs of their own (apparently) exciting lives is that they never crack open a book. To quote Sheldon Cooper in The Big Bang Theory: this is a notion, and a rather sucky one at that. Although I know that I am an unrepentant snob in this area, I feel that if you have no interest in literature, you should just own it, and you should also recognise that you are missing out on an important part of the human experience. At least in part, literature and the arts have led me to live in other countries, to travel, and to meet people with whom I would never otherwise have crossed paths. In many of these areas, there may have been even more crucial motives, but so often the arts are the impetus which set things in motion.